Is a pricing strategy, where products are sold by the firm at a price which is lower than the average cost of production or at a price low enough to make in unprofitable for other players to enter the market.

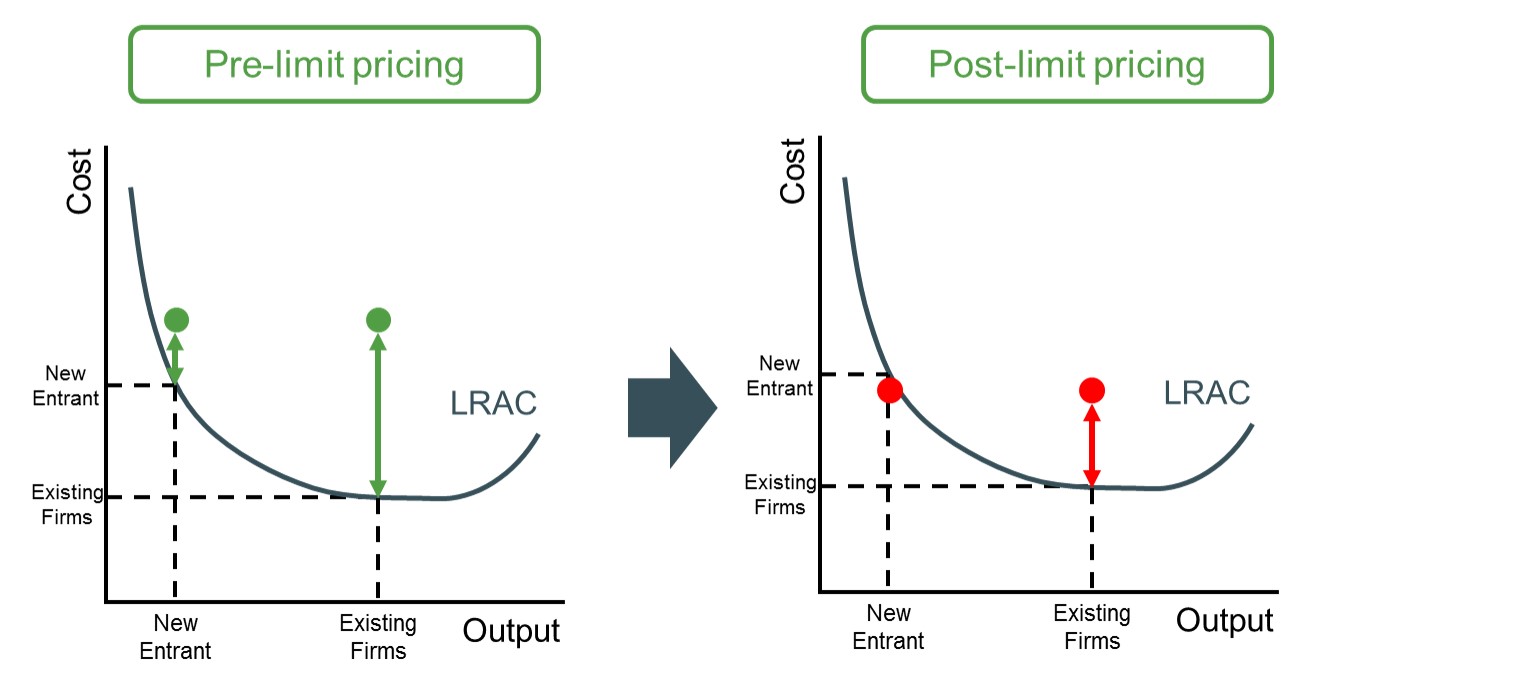

Below is a diagram to illustrate how this type of pricing strategy works. The reason why firms undertake this pricing strategy is to protect their market share and position by successfully deterring new entrants from coming into the market. To do this however the incumbent firm has to sacrifice the amount of supernormal profit they can achieve. In the lefthand side diagram the incumbent has lower costs than new entrants, therefore if they both charge the same price incumbent firms make a large amount of supernormal profit equal to the size of the green arrow. However, new entrants at that price can also make profits due to the price being positioned above their respective LRAC curve (but these profits are substantially lower). So if the incumbent firm did not change the pricing stratey new entrants would always have the profit incentive to enter the market. However, if the incumbent firm takes advantage of their lower costs and charges lower prices to a point which is equal to the point on the LRAC curve for new entrants. These entrants would no longer have any profit incentive to enter the market as they will be charging a price at the marginal cost and just making normal profit. Therefore, incumbent firms sacrifice short-term supernormal profits to guarantee larger long-term profits equal to the size of the red arrow in the right hand side diagram. This is an example of successful limit pricing with the aim to protect and consolidate their market share and position.