Is a market structure that contains a large number of firms selling differentiated versions of a product. As all firms sell differentiated versions of the product being sold, this market structure combines elements from a monopoly and a perfectly competitive market and is therefore classed as a form of imperfect competition.

The main assumptions that are required for a market to be classed as monopolistically competitive are as follows:

- Large number of buyers (consumers) and sellers (firms) - this ensures that a large number of substitutes for the good are being produced.

- Perfect Information - consumers have the ability to assess each product and carry out price comparisons between rival firms.

- No barriers to entry or exit - any firm can enter the market to enjoy profits as there are no barriers of entry present. However, firms can also freely leave the market costlessly if they are making a loss due to no barriers to exit being present. It is this assumption of freedom of entry and exit which means that firms in this type of market structure will always make normal profits in the long-run.

- Firms produce differentiated products - this means that firms can effectively become price makers of their own version of the product, especially if the degree of product differentiation is significant.

If firms operate in a market where all of these conditions are met, it creates an environment of monopolistic competition. This type of market structure is often the most useful from a practical point of view as there are many examples of high-street shops that compete in this way. For instance, the fast food market is an example of a cluster of firms that compete in this way. This is because all firms offer a similar convenient cheap service but offer subtle differences in their service, in order to attract different types of customers, such as: providing different items on the menu, branding and advertising their products in a unique way and designing and planning the interior of their restaurants differently.

Product differentiation is the key feature of this market, as by doing so allows firms to compete for consumers in terms of the quality and individuality of their product rather than just on price. The main aspects of product differentiation available to firms are:

- Branding

- Packaging

- Quality

- Customer Service

- Extra Features

- Skill and Efficiency of Staff

The fact that these firms differentiate their products slightly means that brand loyalty is created amongst their consumers and therefore they face a downward sloping demand curve (AR) rather than the perfectly elastic demand curve under perfect competition. This means that firms can charge higher prices without losing all of their customers - unlike in the perfectly competitive case. But as they still face some close competition from other firms, the demand curve is not equal to the market demand curve, like in the case of a monopoly. The downward sloping demand curve means that if firms wish to sell a higher quantity of the good then they must charge a lower price to do so.

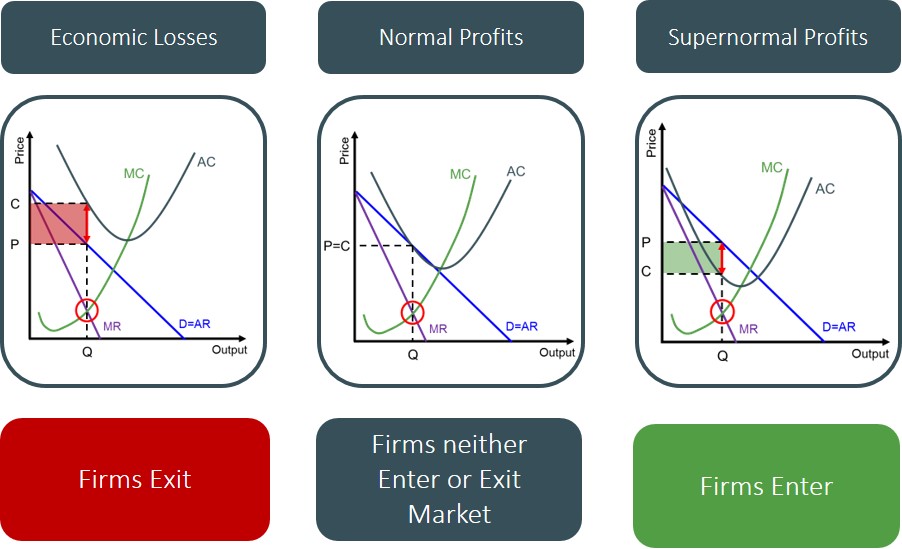

As usual, firms in the market profit maximise where MR=MC and due to the fact that they have some market power as a result of product differentiation, the price that they charge is represented by the price they can set according to the demand curve for that specific quantity of goods. As this price is predominantly above the average cost of production, firms can make supernormal profits. However, it is important to note that supernormal profits are not always achieved n the short-run, as the ability to make profit in the shot-run depends on the position of the firm's average cost curve. This means firms can also make normal profit or economic losses in the short-run as well. The three possible short-run outcomes for firms is shown below:

However, these outcomes only theoretically hold in the short-run as a result of the assumption of no barriers to entry or exit in the market.

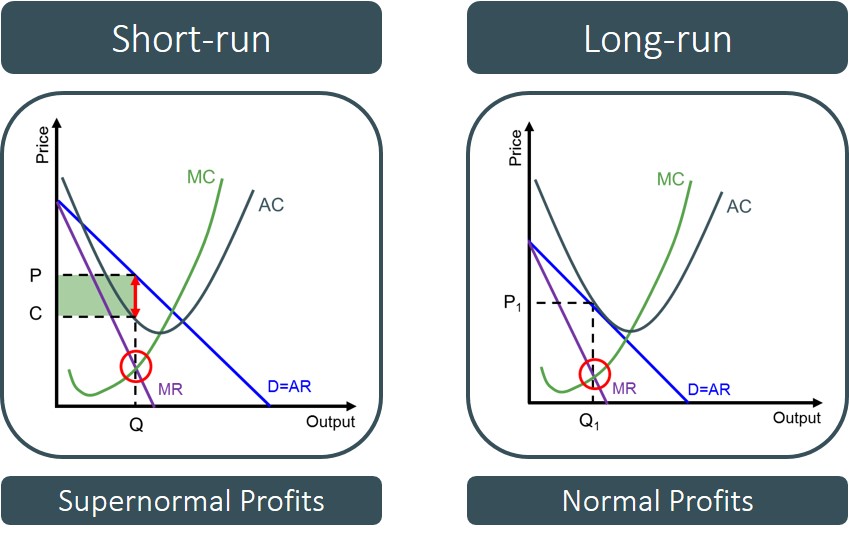

In the case of supernormal profits being made in the short-run, this is eliminated in the long-run because firms outside of the market are incentivised to join and produce because of the attraction of jointly earning supernormal profits. However, as there are only a limited amount of customers in the market, the greater the number of firms in the market, the more diluted the customer base for each incumbent firm becomes. This as a result causes the demand curve and marginal revenue curves to shift inwards, until only normal profits are earned by all firms in the market in the long-run.

The opposite process occurs if firms are making economic losses in the short-run.

When it comes to evaluating monopolistic competition, it is all about assessing the efficiency implications of the market structure and do that we can use the theoretical benchmark of perfect competition.

First of all, productive efficiency is not achieved under this type of market structure as firms do not produce at the minimum of the average cost curve. This is the case in both the short-run and long-run as firms produce at a higher cost when maximising profits. This leads to efficiency and welfare losses that are achieved under a perfectly competitive market structure.

In terms of allocative efficiency, firms in this market structure do not produce where the price is equal to the marginal cost (P=MC). This is because the product differentiation has allowed them to become price makers and therefore can set a price above the marginal cost, to the point specified by the demand curve. This means that compared to a perfectly competitive market, an optimal allocation of resources is not met and as a result a dead weight loss triangle is created in the process. This means that total welfare is higher under perfect competition.

In terms of assessing the market structure for dynamic efficiency and X-efficiency, it all depends on the extent of product differentiation in the market. This is because the degree of product differentiation determines the level and type of competition between firms.

If a product becomes highly differentiated from other products, it effectively becomes a new product on the market. This essentially means that firms have insulated them from any direct competition as there are no close substitutes available. By doing so, the firm has transitioned into a new niche market of which they are the only real providers of this type of good. Doing so, means they start to develop the characteristics of a monopoly and can now engage in setting their own prices without having to take into account the reaction of rival firms, as consumers demonstrate brand loyalty towards this differentiated good and on that basis are willing to pay more for that particular brand. The welfare implications are such that when significant product differentiation takes place, a wide range of products are created for consumers to choose from, which creates more opportunities for them. However, the fact that it could create a specific niche market means that the market may suffer from some of the inefficiencies and welfare losses of a monopoly, which incidentally are more significant than when competing under monopolistic competition. This factor alone could erode away the extra benefits consumers gain from having a wider range of product lines available to them.

On the other hand, if product differentiation is slight, then firms will still have to compete with lots of close substitutes in the market, as the differentiation is not significant enough to distance away from rival products. This encourages firms to have to engage in non-price competition, as price competition could lead to a price war. This though can create dynamic efficiency and X-efficiency as firms need to compete to provide the best product and service in order to convince consumers to buy their version of the product. This in itself, can help drive up the standards of all firms involved by encouraging product innovations (dynamic efficiency). However, this form of dynamic efficiency only occurs if firms use any supernormal profits made in the short-run to pay for research and development projects. Doing so may present firms with an opportunity to become more efficient over time and make supernormal profits in the long run as well.