Is a market structure that describes the conditions required for intense competition to take place amongst firms in an market. This market structure is a contrast to a monopoly market.

The assumptions that are required for perfect competition to hold are as follows:

- Large number of buyers and sellers in the market.

- No individual firm has significant market power to influence the market price - this outcome means that all firms are price takers and have to sell at the prevailing market price.

- All firms sell a homogeneous products - the products that firms are selling are identical in terms of their product characteristics. This creates a horizontal (perfectly elastic) demand curve as all products that firms produce and sell are perfect substitutes for each other.

- Freedom of firms to enter and exit a market - any firm can enter the market to enjoy profits as there are no barriers of entry present. However, firms can also freely leave the market costlessly if they are making a loss due to no barriers to exit being present. It is this assumption of freedom of entry and exit which means firms in this type of market structure will always make normal profits in the long-run.

- Perfect knowledge available to all firms - sellers have perfect knowledge regarding their competitors and possible technological improvements available to the market and consumers have perfect knowledge of all firms prices and therefore will never buy the good at a higher price than at the market price. This assumption reinforces the prevailing market price that all firms must 'take'.

- Perfect mobility of factors of production - factors (e.g. labour and capital) can move from one production process to another to help complete different types of work.

If firms operate in a market where all of these conditions are met it creates an environment of perfect competition. However, perfect competition is often discussed as being just a theoretical model of competition as a result of the unrealistic assumptions that are required to hold e.g. can a market ever have a situation of perfect knowledge across all firms and consumers?

Therefore, despite having a minimal role in terms of practical application, this model of competition is used as a comparison tool against other and more inefficient market structures such as a monopoly or oligopoly. This is because perfect competition leads to an efficient outcome in the long run in which social welfare is maximised, due to firms producing at the point that is allocatively and productively efficient. Therefore, the theory of perfect competition is a good evaluative tool in itself to use as a benchmark to assess the market outcomes from other types of market structure.

A perfectly competitive firms demand curve is perfectly elastic (horizontal) at the prevailing market price, this means two things. First of all the firm can sell as a high quantity of the product they are producing as they want, without impacting the market price. But, the firm has to sell the quantity at the market price otherwise the demand for their product drops to zero. This is because consumers have perfect knowledge about other alternative sellers prices and will always buy the same product from the cheapest possible location.

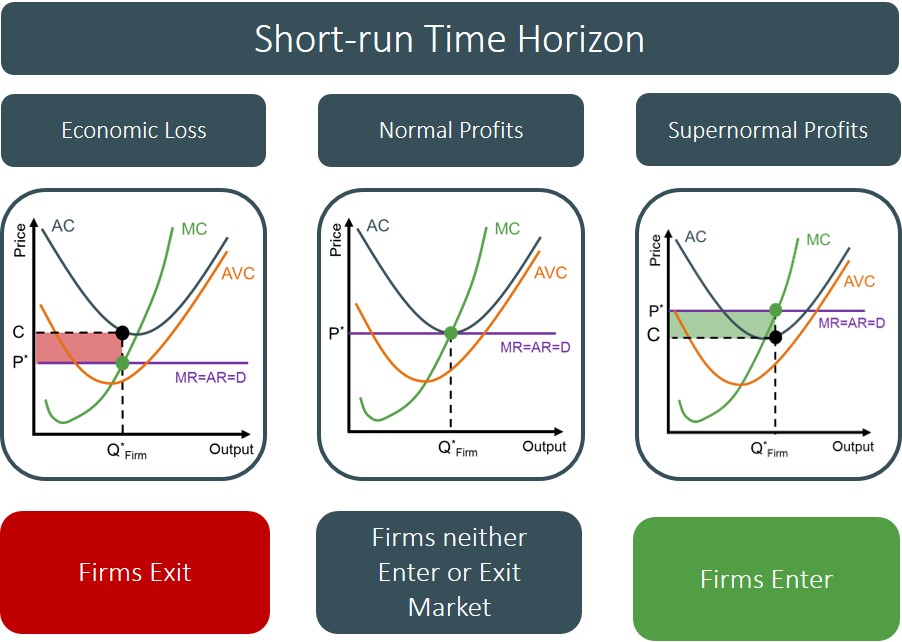

However, when graphically representing the perfect competition market structure for individual firms and the market in general it is important to consider the time horizon that firms are operating in. This is because the efficient outcome of perfect competition is only guaranteed in the long-run. In the short-run, firms produce at the profit maximisation point (P=MC), which can either be above, below or equal to the average cost of production. This means that firms can be making supernormal profit, normal profit or an economic loss in the short-run.

Whether a firm makes a profit or not in the short-run all depends on the type of market that the firm is operating in, the position of the firms average cost curve and the market price that prevails.

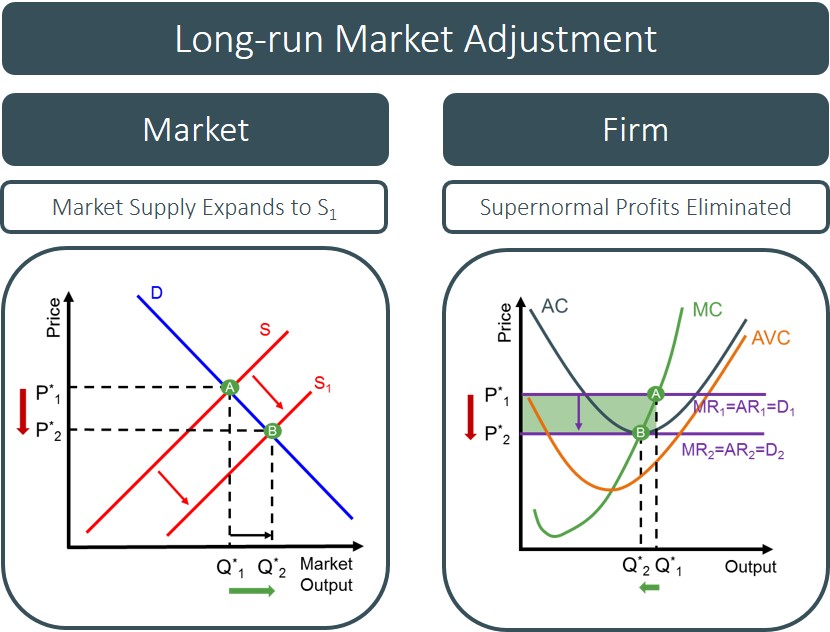

However, in the long-run all firms operating in a perfectly competitive market will make normal profits because of the fact that firms can freely enter and exit the market. For instance, if firms are making a profit in the short-run then this triggers firms that are not currently producing in the market to enter as the presence of supernormal profits lures and incentivises them to start producing. However, the decision for firms to enter increases the supply of goods produced in that market and without an accompanying equal change in demand, this creates excess supply in the market. The excess supply causes the price of the good to fall and as the price determines the position of the perfectly elastic demand curve firms face, this causes the profit maximisation point to fall closer to the average cost of production (which are assumed unchanged). This process of moving down a firms marginal revenue curve causes the amount of profits accruing to each firm to fall. Firms keep entering the market until eventually all supernormal profits have been eliminated and all firms are producing at the minimum of the average cost curve, signalling normal profits. This means all transactions will take place at the market equilibrium price and total output/consumption will be at the market equilibrium level. Below is an example of this market adjustment:

This process works in reverse if in the short-run firms were making an economic loss - firms are incentivised to leave to minimise their losses. In the case of normal profits being made in the short-run no change is made to the market.

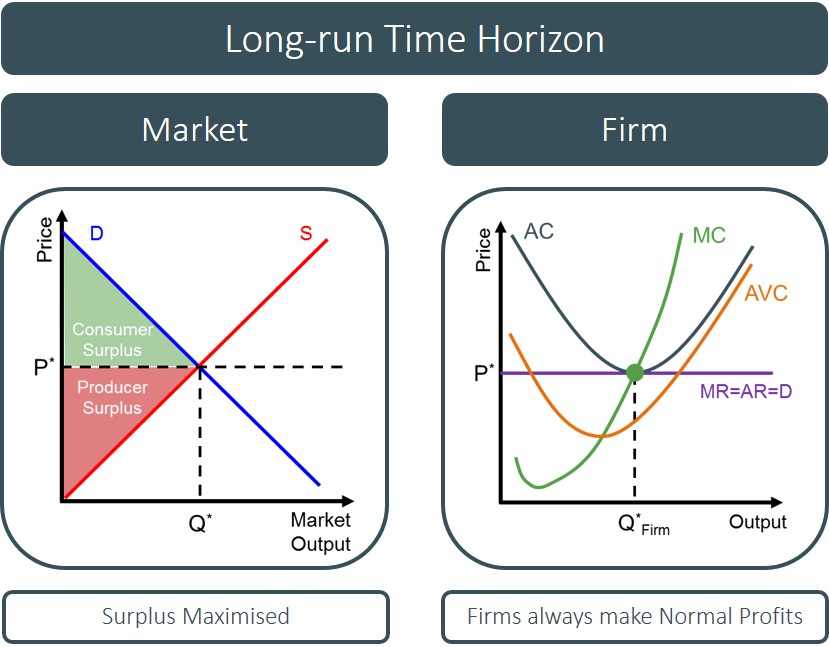

This means the result of all firms in the long-run under perfect competition are shown below:

This outcome is the most efficient market equilibrium that can be achieved because of the fact that there is no deadweight loss triangle present unlike in other market structures e.g. a monopoly.

It creates the most efficient outcome because firms that operate in a perfectly competitive market are classed as productively efficient in the long-run as they end up making normal profits and producing at the minimum of the average cost curve.

Also most firms can be classed as allocatively efficient in the long-run as firms produce at the point where P=MC. However, this only holds if firms are producing in a market with no externalities present. This is because when there are externalities present, private costs and benefits do not equate to social costs and benefits. If the marginal social benefit and costs do not equate then this means that consumer and producer surplus cannot be maximised and this means there must be a better allocation of resources available in the market.

However, despite perfect competition providing efficient results, one type of efficiency that is not achieved is dynamic efficiency. This is because in order for firms to be incentivised to achieve dynamic efficiency they need to make supernormal profit to enable them to undertake the investment required for the research and development needed to innovate the production process. It is unlikely that this will be achieved in perfect competition because the assumption of perfect knowledge across all firms means that firms can just replicate any new products or new techniques developed in the production process, removing any competitive/cost advantage this type of investment is meant to develop. Also the fact that firms cannot make supernormal profit in the long run means that they will never be in a position to be able to protect the advantages of their investment and will not be encourage to make the changes required. The fact that dynamic efficiency is not achieved creates wider implications for the economy because it is investment that drives the long-run trend growth rate and therefore if investment is stunted because of this form of competition, long-run growth will be permanently revised at a lower level.

The final point to mention regarding perfect competition is the theoretical model can be used as a yardstick to compare other market structures against. This is because in reality industries are never really perfectly competitive, but by relaxing some of the assumptions of perfect competition it may mirror some types of market structures (e.g. monopolistic competition) and therefore allow us to asses and evaluate those markets. For instance, the closer an industry is to perfect competition, the closer it is to the efficiency results which fosters improved services and products.