When the percentage change in demand is less than the percentage change in price. In this case the PED elasticity value will lie between 0 and -1.

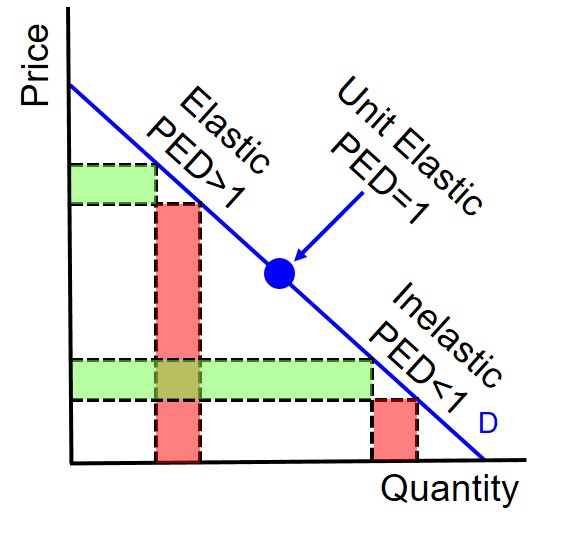

To identify the shape of an inelastic linear demand curve we do not focus on the gradient of the curve as this does not actually determine elasticity. Crucially, it is the position of the demand curve that determines elasticity. This is because all linear demand curves contain portions on the curve which can be classed as elastic, inelastic and unit elastic. Any demand curve shown (like the one below) is just a section of a much larger demand curve that extends beyond the axis.

So effectively we can see that the midpoint of the demand curve is when unitary elasticity is achieved. The bottom half of the curve is inelastic, because if the price rises - at any point below the midpoint - expenditure increases despite a quantity fall. The top half of the curve is elastic, because if the prices rises - at any point above the midpoint - expenditure decreases due to a large quantity fall.

Therefore, the easiest way to determine an inelastic demand curve is to extend the section of the demand curve drawn and identify which axis it intersects. If the demand curve intersects the x axis we can judge it as being an inelastic demand curve as we must be focusing on the bottom of the demand curve. An example of an inelastic demand curve is shown below.

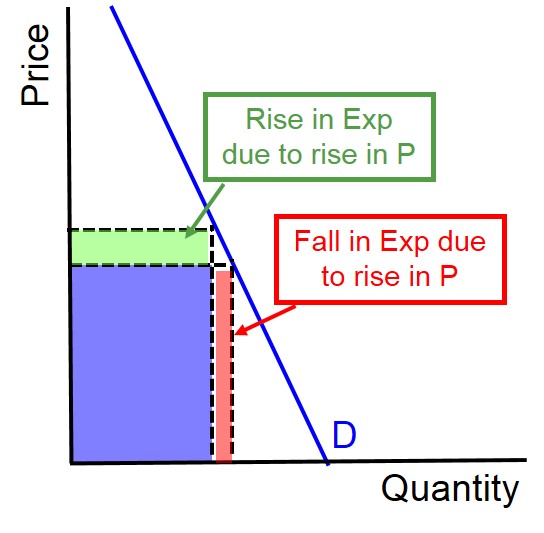

This diagram highlights the changes in expenditure for a producer that occurs when there is a small price rise in a market with inelastic demand. When a demand curve is relatively inelastic, it means that consumers are price insensitive to changes. In this instance, a price rise leads to a small fall in demand as consumers refuse to switch to alternative cheaper substitutes.